013: Hostage to the Process

You've probably seen this EM: operates fine when policy is clear, but freezes in ambiguity. Asks permission for decisions in their scope. Seeks templates for situations requiring judgment. They're not bad people, they're just hostage to the process. And it costs more than what you think!

Last month, an EM in the org Slacked in a group: "Hey, can the group set up time to talk about when teams should write an ADR versus an RFC? I know we have the guidelines, but they don't cover this case. I want to make sure I'm giving my team the right guidance."

I pulled up our documentation. We do have guidelines. They're pretty clear: RFCs for cross-team architectural decisions, ADRs for team-level significant choices. But this EM's situation was in the gap: a decision that might affect one other team, maybe, depending on how things evolved. The guidelines didn't have a footnote for "medium-sized decision with unclear blast radius."

They wanted us to make the guidelines more complete. To patch the gap.

But here's the thing: the guidelines will never be complete. They can't be. There will always be edge cases, ambiguous situations, judgment calls. And when you hit those gaps, you need to make an intuitive call based on what you know.

This EM couldn't. They were paralyzed by the gap in the flowchart.

I see this pattern everywhere now. Engineering managers who operate fine when the policy is clear, but freeze when they hit ambiguity. They're not asking "what do you think I should do?", they're asking "can you update the policy so I don't have to think about this?"

They're hostage to the process.

The Pattern

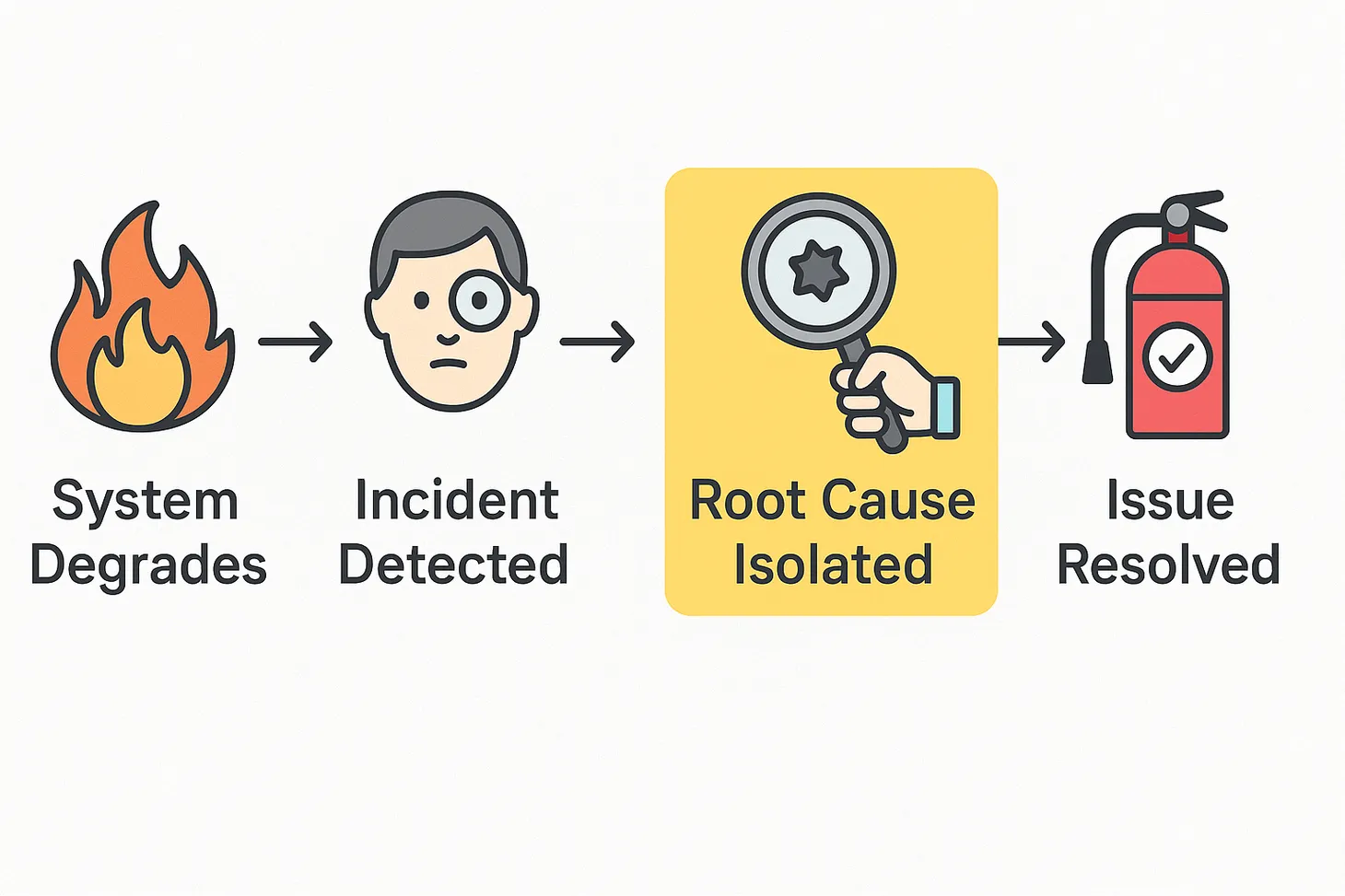

Here's what it looks like in practice: An EM knows something needs to happen – a difficult conversation, knowing when to to deploy and when not to deploy, a team restructure, a performance improvement plan. But instead of acting on that knowledge, they seek external validation. Not because they lack information. Not because they genuinely don't know what to do. But because they're uncomfortable operating in the space between "clear policy" and "total ambiguity."

They want the flowchart to be complete. They want every decision to have a precedent. They want permission.

It is not about lacking information. It's about lacking something deeper: the willingness to make predictions and test them. To explicitly think through "if I do X, what will happen?" and then actually observe what happens and learn from it.

Ben Kuhn has this useful framing in his essay on impact, agency and taste. He talks about taste as "the quality of your predictive models and your search heuristics." But the key insight is how you develop that taste. You develop it by explicitly asking yourself: "What do I predict will happen if I choose option A?" Then you unroll the trajectory. Even if you think you're already intuitively predicting outcomes, forcing yourself to be explicit helps you realize things you missed.

One of Kuhn's manager role models does this: every time Kuhn asks for advice, the manager asks back "what do you think will happen?" And Kuhn says it's "kind of silly how often it helps me realize something new." Then, and this is crucial, you revisit your predictions afterwards. What did you predict? What actually happened? Update your model.

For EMs, this is the difference between "I think we should do an RFC here because I predict the platform team will push back if we don't involve them early, and that'll delay us by two weeks" versus "The guidelines don't explicitly cover this, so I need to ask someone what to do."

The EMs who are hostage to the process aren't making predictions. They're not testing them. They're not updating their models. Every situation that doesn't match the flowchart is just... a gap they need someone else to fill. They're not learning from the data because they're not generating data. They're just waiting for someone to tell them what the complete flowchart says.

The Failure Modes

Let me break down the possible failure modes of this. These aren't always distinct categories, to be fair. Often you see several at once, but naming them helps.

1. Lack of Agency

This EM genuinely believes they need permission for decisions that are well within their scope. Not because there's a policy requiring approval, but because they've internalized "check first" as their default mode.

I watched an EM spend three days trying to schedule a "decision meeting" about whether their team should have a design review for a new API. Not a meeting to have the design review, mind you – a meeting to decide if they should have one. They'd asked two peer EMs, their skip-level, and me.

When I asked "What do you think?" they said: "I mean, I think we should, but I wanted to make sure that's the right call."

The team needed the design review. The EM knew they needed it. But they couldn't just... schedule it. They needed someone to validate their judgment first.

The tell: they use phrases like "I wanted to run this by you first" for decisions where the answer should be "You don't need to run this by me."

2. Lack of Taste

These EMs can't predict outcomes. They don't know which interventions will work because they haven't built mental models from experience. So every situation feels equally uncertain, and every decision feels equally risky.

You can see this in 1:1s. I'll ask: "What do you think will happen if you give Marcus that feedback about his communication in standups?" And I get: "I'm not sure. What do you think?" Or worse: "What's the standard approach for this?"

There is no standard approach. Marcus is a specific human with specific patterns. If you've been managing them for six months, you should have some hypothesis about how they'll respond to direct feedback versus written feedback versus public recognition versus private correction.

Here's another example that illustrates this point: An EM came to me worried about an engineer who'd missed two sprint commitments in a row. "Should I put them on a performance improvement plan?"

I asked: "Why did they miss the commitments?"

"They got pulled into production issues both sprints."

"Okay, so what's the actual problem you're trying to solve?"

Long pause. "I don't know. I just know missing commitments is bad, and I thought there was probably a process I should follow."

They had no model of what was actually happening. They'd pattern-matched "missed commitments" to "performance problem" without thinking about context, causation, or what outcome they actually wanted.

Or this: A senior leader mentions in passing that PR reviews seem slow across engineering, and suggests "maybe teams should try open office hours for reviews." An EM hears this and immediately implements it. No questions asked. No thinking through whether their team's PR reviews are actually slow, or what's causing the slowness if they are, or whether office hours would address that cause, or what the tradeoffs might be.

Two weeks later: "The office hours aren't working. Should we try something else?"

"What problem were you trying to solve?"

"I don't know, [senior leader] suggested it."

This is cargo-culting. They heard a solution from someone senior and implemented it without predicting what would happen. They didn't ask: "What's our actual PR review situation? Is it slow? Why? Will office hours help? What do I predict will happen if we do this?" They just... did it. Because someone suggested it, and implementing suggestions feels like action.

Taste isn't about always being right. It's about having a model you can test. "I think Marcus will be defensive initially but will process it overnight and come back with questions" is taste. "I don't know, that's why I'm asking" is its absence.

3. Lack of Autonomy (Confused with Permission)

Here's a subtle one: confusing autonomy with permission. Autonomy isn't "my manager said I could." Autonomy is "I have the context and capability to make this call, and I'm making it."

I see EMs who've been explicitly told "You own team composition decisions" still asking permission to move someone between projects. They've heard "You have autonomy" but they're still operating in "get approval" mode.

The difference shows up in how they frame decisions. Compare:

"I want to move Jamie to the infrastructure project. Is that okay?"

versus:

"I'm moving Jamie to the infrastructure project. Here's why: she's been asking for more backend work, the infra team needs someone with her API experience, and it solves our load balancing problem. I'm watching for: whether she gels with that team's style, since they're much more async. I'll update you in two weeks on how it's going."

One is seeking permission. The other is informing and inviting correction if needed. Same decision, completely different mental model of how autonomy works.

4. Self-Preservation Mode

Some EMs have learned, often the hard way, that the safest thing is to always have someone else's fingerprints on a decision. If it goes wrong, they can point to the process they followed, the approvals they got, the consensus they built.

I once watched an EM spend three weeks "socializing" a decision to pause work on a feature that clearly wasn't working. The engineers knew it. The PM knew it. The EM knew it. But instead of just making the call, they scheduled "alignment meetings" with four different stakeholder groups, created a decision document with a RACI matrix, and got written sign-off from two levels up.

When I asked why all the overhead for what should have been a straightforward call, they said: "I just want to make sure everyone's on board so there are no surprises later."

But that wasn't it. What they meant was: "I want to make sure if this turns out to be the wrong call, I can show that everyone agreed to it."

This is the EM who never just does something. They "socialize" it first. They get "alignment." They document the "decision-making process." Not because these things add value, but because they create a paper trail that says "I followed the rules" and more importantly, "other people agreed with me."

Every decision gets routed through "how do I protect myself if this fails?" instead of "what's the right thing for the team?"

The most toxic version: EMs who actively avoid making judgment calls because judgment calls can be questioned. Process compliance can't. "I was just following the process" is a shield. "Everyone signed off on this" is a shield. Taking responsibility for a decision? That's exposure.

5. Inverted Priorities (Me > Team > Org)

Most EMs understand intellectually that the priority should be org > team > me. But when hostage to the process, this flips. They optimize for their own safety, comfort, or metrics rather than what the team or org needs.

Here's how it manifests: An EM has a high performer who's clearly miserable and would thrive on a different team. The right move is obvious - help them transfer. But that EM is worried about losing their "top performer," about how it'll look in their next calibration, about whether their director will think they "can't retain talent."

So they stall. They ask: "What's our process for internal transfers?" They need to "think about team composition." They schedule meetings to "discuss the situation."

Meanwhile, the engineer gets more miserable and starts interviewing externally. When they leave the company entirely, the EM says: "I was trying to figure out the right process for helping them transfer, but they left before we could work through it."

Or: An engineer needs difficult feedback about collaboration issues that are hurting the entire team. Three other engineers have complained. The team's velocity is suffering. But delivering that feedback might make the EM's 1:1s uncomfortable for a few weeks. So they wait. They ask for coaching on "how to deliver hard feedback." They look for a template. They schedule prep meetings with HR.

The team suffers while the EM protects their own comfort.

6. Process-as-Security-Blanket

Some EMs have mistaken process for competence. They believe that if they can just find and follow the right process, they'll be good managers. That management is about correctly executing procedures rather than making judgment calls.

This shows up as: "Can you send me the template for..." or "What's the standard way we..." or "I want to make sure I'm doing this correctly."

I had an EM ask me: "What's our process for deciding if an engineer is ready for senior?" I sent them our engineering career ladder. They came back: "Right, but what's the process? Like, what steps do I follow?"

They wanted a checklist. A rubric with objective scoring. Something that would make the decision mechanical.

But promotion decisions aren't mechanical. There's no template for "this engineer has the technical depth but not quite the scope" or "they're operating at senior level on their current team but I'm not sure they could do it on a harder problem." These are judgment calls informed by context, comparison to other engineers, and prediction about future growth.

The EMs who are hostage to process are looking for the instruction manual that doesn't exist.

7. Can't Tolerate "It Depends"

This might be the most fundamental failure mode: discomfort with "it depends" as a valid answer.

These EMs want binary rules. "Should we always do X?" "Is Y ever okay?" "When exactly should we do Z?"

But engineering management is made of "it depends." Should you give that feedback in writing or in person? It depends – on the engineer, the feedback, your relationship, their preferred communication style, the urgency, and six other factors.

Should that decision be an ADR or an RFC? It depends.

Should you intervene in that team conflict or let them work it out? It depends.

Should you hire for this gap or grow someone internal? It depends.

The EMs who can't tolerate this ambiguity spend all their energy trying to eliminate it. They want rules that will never require judgment. But judgment is the job.

The Real Cost

The cost of this failure mode isn't just slow decisions or bureaucratic overhead. It's deeper.

Teams stall. When engineers need something and their EM says "let me check if we have a process for that," momentum dies. The engineer learns: don't bring problems to your manager; they'll just create more process overhead. I've seen teams start routing around their EM entirely, making decisions in Slack and backfilling the manager later.

Talent leaves. Good engineers can smell when their manager is administering rather than leading. They lose respect. They find managers who can make calls. I've seen multiple exits that came down to: "My manager couldn't just make decisions. Everything required meetings and approvals and checking with their manager. I don't have time for that."

You become the bottleneck. If your EMs can't operate without you, you're not scaling leadership, you're creating a dependency hierarchy. Every decision flows up. Your calendar fills with "quick question" meetings that shouldn't need to happen. You're doing their job and yours.

Culture of learned helplessness spreads. When EMs model "always check first, never trust your judgment," their engineers learn the same pattern. Soon you have an entire org that can't ship anything without three levels of approval. The most junior engineers start asking permission to rename a function.

Perhaps most damaging: the org stops learning. If no one's making judgment calls, generating data, and updating their models, everyone's taste stays underdeveloped. You get process accretion – every edge case becomes a new policy, every failure becomes a new approval gate – but no actual wisdom.

The system doesn't get smarter. It just gets slower.

Breaking the Cycle

So what do we do about it? Let's split this into two perspectives: what the EM can do, and what you (as their manager) should do.

For the EM: Developing Taste

If you recognize yourself in these patterns, here's the hard truth: no one's going to give you permission to have better judgment. You have to build it.

Start making small bets. Pick decisions that are low-stakes but require judgment. Should you change the team's meeting schedule? Should you give that engineer the stretch project? Should this be an RFC or just a Slack post? Make the call. Don't ask permission. Watch what happens. Update your model.

Ben Kuhn's point about taste is that it comes from iterations. You need reps. Every time you make a judgment call and observe the outcome, you're refining your predictive models. But you can't refine models you're not using.

Do post-mortems on your decisions. Not just the failures, also the successes. After you have a difficult conversation, ask yourself: What did I predict would happen? What actually happened? What surprised me? What will I do differently next time?

This is how taste develops: deliberate reflection on your predictions versus reality. If you predicted the engineer would be defensive and they weren't, that's data. Update your model of that engineer. Update your model of how people respond to feedback. Wring out every possible update from the data you get.

Seek feedback on your judgment, not your compliance. Instead of asking "Did I follow the right process?" ask "Do you think that was the right call?" or "What would you have done differently?" Focus on the quality of your decision-making, not the correctness of your paperwork.

Build your own frameworks. You don't need the company's official template for every situation. Create your own mental models. When I'm deciding whether an engineer needs feedback, I have a simple framework: Is this a pattern? Is it affecting others? Can they change it? Is this the right time? That's my heuristic. It's not official policy. It's just taste I've developed over fifty similar decisions.

Embrace the discomfort of "I think." Practice saying "I think we should do X because of Y" without adding "but let me check" or "unless you think otherwise." Own your judgment. You'll be wrong sometimes. That's fine. That's literally how you learn.

Get comfortable saying "it depends" and then actually doing the depending. "Should we do an RFC? It depends – this affects the platform team, so yes. Let me set it up."

For the Manager of Managers: When to Coach, When to Exit

Now the harder question: What do you do when one of your EMs is hostage to the process?

First, diagnose which failure mode you're dealing with. Lack of taste is coachable – they just need more reps with reflection. Lack of agency is coachable – you can gradually expand their scope. Self-preservation mode and inverted priorities are much harder. Those are often about fundamental values misalignment or deep insecurity that's beyond your scope to fix.

For lack of taste: Coach through joint decision-making. Don't just tell them what to do. Walk through it: "What do you think will happen if we do X? Why? What data are you using to predict that? Okay, let's try it and see." Then debrief afterward. You're teaching them to build and test models, not just follow instructions.

For lack of agency: Gradually increase their scope without permission gates. When they ask "Can I do X?" respond with "You don't need to ask me that, you own this. What's your thinking?" Push the decision back. If they make a bad call, debrief what they learned, but don't make them regret taking initiative. You want to reward the decision-making muscle, even when the outcome isn't perfect.

For self-preservation mode: This is trickier. You need to reset the incentives. Make it clear that you value good judgment over perfect compliance. Celebrate smart risks even when they don't pan out. If they're optimizing for covering their ass, they've learned — from you or from the org — that's what gets rewarded. Prove otherwise.

But also: sometimes this is unfixable. If someone's been burned badly enough that they'll never trust their own judgment again, they might need a different environment.

For inverted priorities: Have the direct conversation. "I've noticed you seem more concerned about your metrics than about doing right by the engineer/org. Talk to me about that." Sometimes this is coachable – they just needed the explicit priority reminder. Sometimes it reveals they're not aligned with how you expect leaders to operate.

The manage-out decision: Here's the uncomfortable reality: every org has a configuration space of behaviors it can accept. How much autonomy? How much nuance? How much judgment-versus-process?

If you're in a high-autonomy org that values nuance, and you have an EM who will only operate in "show me the flowchart" mode, they're not a fit. You can coach for a quarter or two. But if they're fundamentally uncomfortable with judgment calls, and your org requires judgment calls multiple times per day, you need to help them find an environment that's a better match.

I'm not saying give up on people quickly. I'm saying recognize that some people thrive in high-process, low-ambiguity environments. They're not bad managers; they're just matched to the wrong context. If you're at a startup that needs people to figure things out in the gaps, and they need everything specified, that's a mismatch. If you're at a large enterprise with well-defined processes and they want to make intuitive calls, that's also a mismatch.

The signal to watch for: If after several months of coaching, you're still the one making all their decisions for them, if they still can't operate without your approval, if they're still asking permission for things clearly in their scope – it's time to have the hard conversation.

Not "you're failing" but "I don't think this environment is set up to let you be successful. You seem to need more structure than we can provide" or "You seem to need more clarity than exists here, and I don't think that's going to change."

Some people will hear that and level up. Some will hear that and realize they need a different role or different company. Both outcomes are better than letting them stay in a role where they're perpetually uncomfortable and underperforming.

What Are You Optimizing For?

So here's the question I'd ask you to sit with: If you're an EM reading this, have you been optimizing for safety over impact? Have you been collecting process compliance receipts instead of building judgment?

When you hit the gaps in the flowchart – and you will hit them, constantly – can you make a call? Or do you freeze and wait for someone to patch the gap for you?

And if you're managing EMs: Are you creating the conditions for your managers to develop taste? Or are you inadvertently training them to seek permission by making them regret every decision they make without checking first?

The process is a tool. It's useful. It provides guardrails and consistency. But it will never be complete. And in the gaps, which is where most of actual management happens, you need judgment.

If you're hostage to the process, you're not managing. You're administering. And your team deserves someone who can make calls in the ambiguity.

Old School Burke Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.